Focus groups are the most widely used method, but that does not mean they are always the right one.

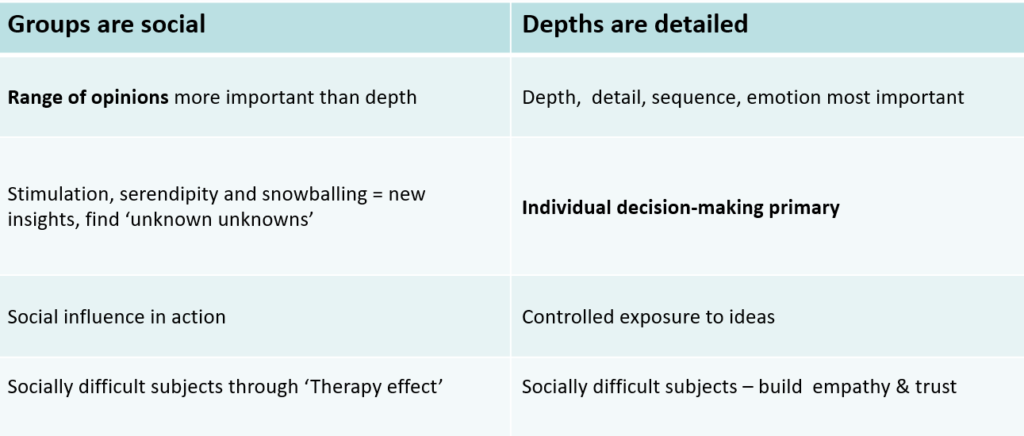

The guide to choosing focus groups or depth interviews

When should you do depths?

- When detail, sequence, and emotion most is important

- You need opportunity for extensive probing

- Uncontaminated responses, no peer group pressure

- Individual decision-making is important – people may take different routes through the same material ( e.g. website research)

- Socially difficult subjects – you can especially build empathy & trust 1:1

- Controlled exposure to ideas; other people can’t pre-empt or derail your strategy

- When people can’t or won’t attend a group – very busy, very senior, concerned about sharing privileged information, etc.

BUT

- Depths can be experienced as more intrusive and self-revealing – there is nowhere to hide.

- A good relationship with the interviewer is important for trust and disclosure

- Relatively expensive – a lot of resources for a small sample size

- More material and individual detail to analyse

When is it better to choose groups?

- When you are interested in a range of opinions and happy for people to share them with each other

- You want some creativity, as group members stimulate new ideas and thoughts between each other

- You want to observe how people influence each other and change their attitudes

- Groups on certain ‘difficult’ subjects give individual members support ( e.g. cancer) or normalise behaviour (e.g. a group of fare evaders works well when they all realise they do the same thing)

- You haven’t the money or time for depths and you need a reasonable size sample.

And should you need to observe behaviour as part of your research, you can ask people to bring photos or videos / to keep a diary / if you can observe the relevant behaviour before, during or after the interview.

More detailed stuff

Useful if you are writing a proposal and need to justify your choice of methods.

In any project, you have a choice of using

- Interviewing – in groups and depths, face to face and mobile/online, which also offers ‘in the moment’ and longitudinal methods

- Observation – great for nonconscious, automatic, habitual, natural behaviours

- Ethnography – a social and cultural perspective on the context of the individual

- Collaborative methods such as workshops, co-creation, design thinking

- Cultural/ semiotic analysis

- Experimental method – as in psychology experiments

- Technological enablers – eye/mouse tracking, facial coding, etc

And of course mixed methods, where each compensates for the weakness of the other, as well as extending methods with pre and post-tasking.

‘Methodology’ is the study of the principles and assumptions underlying the research methods – the justification and explanation for the use of particular tools.

Benefits

- People can tell their own stories in their own words, describe their experiences, priorities and frames of reference.

- Although interviewing is a social context with its own rules, it’s similar to ordinary conversation. A good introduction clarifies the rules and most people are comfortable with them.

- Respondents may gain insights about themselves and often regard the process as informative and interesting.

- Most Interviewing methods are flexible, responsive, can focus on emotions, build upon knowledge, ideas, and hypotheses – and generate data that can be easily analysed for content and meaning.

- They also allow for the use of projective and enabling techniques that help people access some of the things they can’t put into words.

Drawbacks

We assume respondents have access to their needs, feelings and experiences and can tell us about them. But it may not be as accurate and authentic as we imagine. Its a myth that people can tell you what they want

Verbal reports are often ‘good enough’ for a general understanding of motivations and behaviour, but are limited if you need accuracy, because of:

- Biases in memory. “The event of a memory is not the same thing as the memory of an event.” Memories are not accurate records; they are influenced by context, emotion, and suggestion.

- Limits to self-awareness, of habitual behaviour, cultural norms, heuristic decision-making, and personal traits and motivations. Research shows that when people don’t know something they offer a rationalisation.

- There are nonconscious processes of automaticity, implicit learning and tacit knowledge . For example, people can be surprisingly accurate at evaluating competence, trust, likeability etc, but they cannot describe how they arrived at those judgements. Thin Slices – first impressions

- Stereotyping is also nonconscious, and can contradict stated conscious attitudes.

- We have a ‘Psychological Immune System’ (Timothy Wilson) of cognitive biases that add up to create an image of ourselves as more competent and better people than we really are. We overestimate ability at work, consistency and accuracy of our choices, the amount of control over events, and we (often unconsciously) blame others for our mistakes.

- Rationalisation Several experiments have shown however that people will always provide an explanation for their behaviour, even if they are describing choices they did not actually make. Johansson choice blindness lab

- Interviews don’t account for situational influences. Situational influences are temporary conditions that affect how buyers behave. They include physical factors, social situations, moods, lighting, and even scent. Only a small part of this is available to people sitting calmly in a group discussion room.

- People are poor at predicting their behaviour. They fail to take situational factors into account. When they are in a ‘cold’ state (as in many research situations) they cannot imagine how they would act in a ‘hot’ (emotional) state. They overestimate their willpower, their kindness to others, and willingness to help. Better at predicting others

- The social context of interviewing leaves the respondent open to influences from the interviewer, and in a group, from other respondents. In groups there is an element of social theatre and impression management.

How to overcome these?

Be clear about how much any of these drawbacks matter to the usefulness of your research. If any of them do – aim to compensate.

- Use projective and enabling techniques to surface non-conscious attitudes and emotions; or use other methods such as the Implicit Association Test

- Use checks on behaviour and observation of habits

- Use bracketing and best practice in interviewing to minimise influence

- Find ways of bringing in situational influences – enhanced recall interviewing, stimulus material, observational research

- Be aware of cognitive biases when planning and interpreting the research

- Include questions that will help you assess social factors and influences on the individual

- Use semiotics to help with a cultural framework

- Ask people to think about how other people would predict their behaviour.

For a full understanding of how Projective and Enabling techniques can help surface the nonconscious, see The Source – The Qualitative Technique Sourcebook

Groups are cost- effective, flexible, emotionally responsive, creative, and allow for the use of projective techniques and stimulus material. They are innately a social method and lose many of their benefits when moderators are over-controlling and insist that respondents should not influence each other.

Different types of groups:

- Standard: in Europe, 6-8 respondents for 1 1/2 to 3 hours, a topic guide but some freedom to diverge. Some analysis afterwards.

- US Focus group: can be the same are European, or involve 12 or more respondents, highly structured questions, ‘hands up type answers; analysis by the clients who are viewing. (These are two different and equally valid models, as described by Mary Goodyear. ) Goodyear, M, (1996) Divided by a Common Language: Diversity and Deception in the world of Global Marketing, Market Research Society Conference

- Unstructured / non-directive – or just very lightly moderated for very exploratory work

- Mini group – shorter in time and or numbers, for more focus on people or a single topic

- Extended creativity groups – longer, for more techniques. Merging into workshops.

- Reconvened groups/ qual panels – asking the same respondents back two or three times, with tasks in between. They work really well together after the first group. Expensive to do face to face, often has an online component now.

- Sensitivity groups with respondents trained for self-insight. A fascinating experiment by Bill Schlackman.

- Conflict Groups – managed workshop style where opposing sides present their cases

- Turnstile or stacked groups – when people don’t want to talk about a subject or might have little to say (e.g. about why they don’t use particular products or features), they first watch another group of users talking about the issues. They then go through a metaphorical turnstile into the group room and have their own discussion.

- Mobile, multi-location groups – for comparing say, retail or entertainment experiences. Hire a luxury coach with swivel seats and capture experiences while travelling from one to another. Online mobile research is the current alternative, but this captures more emotion and context as the researcher is more involved.

- Family and peer groups – the natural context for a lot of decision-making. You just have to let go of the idea that you don’t want people to influence each other in groups – that is what they are all about.

See the online section for hints and tips on how to run groups online

Summary of Advantages of groups (After Hess 1968)

- Synergism – the information produced is more than the sum of its parts (the individuals taking part)

- Snowballing – participants can trigger a chain of responses; data emerges through interaction

- Stimulation – people become involved as the group warms up

- Security – no individual feels pressured to answer, they can ‘hide’ in the group.

- Spontaneity – people can speak up when they have something to say

- Serendipity – relevant ideas can arise and be explored ‘out of the blue’

- Specialisation – a specially trained moderator should be used

- Scrutiny – the group can be viewed, taped and analysed; interpretation can be checked.

- Structure – most groups follow a structure to meet their objectives

- Speed – they are faster and more cost-effective than depth interviews

Additionally, they are Social – they show how social processes such as influence, co-operation, validation, decision-making, role and status operate and develop.

The drawbacks (not mentioning the general issues described in talk-based methods) include:

- Need for a skilled moderator to manage group process, people, and norms to avoid groupthink and uneven levels of contribution

- Less detail about individuals; especially if their influences, processes and reactions vary

- ‘Contamination’ of response – when unexpected new information/ideas are introduced

The clear alternative in the last two cases is to do depths. Online groups minimise group processes and groupthink but often at the price of group interaction.

Types of depth interviews

- Standard – 20/30 – 60 mins

- Telephone – or webcam

- Paired– usually friendship pairs, but you can also recruit people with different points of view

- Stream of consciousness – For immediate reactions as they are experienced (Kahneman’s system 1)

See: Alan Swindells, Invisible Mechanics of Consumption, MRS 2000 Conference - Unstructured – in reality loosely structured around a topic or activity

- Cognitive or enhanced recall – developed by Fisher and Geiselman to help the police take more accurate witness statements and is a robustly tested method. Use when you need more accurate recall but the event has not been captured. The Cognitive Interview method of conducting police interviews: Eliciting extensive information and promoting Therapeutic Jurisprudence by Ronald P. Fisher, R. Edward Geiselman

- Laddering – a really powerful method for moving from basic attributes to higher level benefits or consequences. Its described under Projective techniques although it is not technically a projective.

- Motivational or change process interviewing – with specific underlying models of the process, that includes checking the disadvantages of letting go of the old behaviour. Ref: Botelho RJ (2001) www.MotivateHealthyHabits.com

- ZMET – Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique is a licensed system created by Gerald Zaltman. It starts with consumers being asked to bring pictures that represent how they feel about the topic. Collaging on steroids and with much more analysis. See http://www.olsonzaltman.com/process.htm

When should you do depths?

- When depth, detail, sequence, emotion most is important

- Opportunity for extensive probing

- Uncontaminated responses, no peer group pressure

- Individual decision-making primary

- Socially difficult subjects – build empathy & trust

- Controlled exposure to ideas

- When people can’t or won’t attend a group – very busy, very senior, concerned about sharing privileged information, etc.

BUT

- Depths can be experienced as more intrusive and self-revealing – nowhere to hide

- Good relationship with interviewer is important for trust and disclosure

- Expensive – a lot of resources for a small sample size

- More material and individual detail to analyse

In some sectors, e.g. doctors, depth interviews are a standard method but don’t work as well as they could. This is because of rigid, boring and repetitive topic guides, time pressures, lack of effort to build empathy and previous negative experiences. This paper, Doctors Eat Ice Cream too, is a reminder that doctors are part of a cultural tribe but are also human, and respond to research approaches that honour both of these.

“Most of the most interesting things happen in participants’ lives when the researcher isn’t there” Steve August

This method focuses on the use of mobile devices to document the experiences of the user. Also called contextual research, it captures the behaviour, emotions and experiences as they occur – or as soon as it is realistically possible to photograph or film them.

The immediacy brings the researcher closer to System 1 thinking but unlike face to face observation, it is less intrusive. It also helps close the empathy gap (which is when its hard to remember what it was like to be in a certain state when you are in a completely different one.) There is however a platform for organising and analysing all this data.

To work with this, you need to think differently about your ‘guide’

1.Activity/ Behaviour – what is happening / what are you doing

2.Context – where are you? Who are you with?

3.Emotion – how are you feeling?

It is also important to set up the tasks clearly with participants, create tags and remember that they will self-edit and occasionally give performances or rationalisations. Nevertheless it is clearly closer to real life than sitting on a sofa or at a computer and describing what happened.

Wearable cameras

Few people are able to accurately report their behaviour in detail, so when that is important a wearable camera can be set to take a photographic record at regular intervals – every 30 seconds for example. The photos are geotagged, and can be downloaded at the end of the day.

The wearer ought to have a sign notifying others of the recording, to comply with the Code of Conduct.

The wearer ought to have a sign notifying others of the recording, to comply with the Code of Conduct.

To the right is the Lifelogger, far right the Narrative Clip, and there are many others on the market.

The amount of detail is astonishing and very few behaviours would not make it on record. It seems to be more publicly acceptable than Google Glass (there is no audio – yet).

One of the main issues is the sheer amount of data, although the associated app is able to cluster the photos. The researcher has to review the output, select the scenes of interest, and then interview the wearer to understand the significance of the observed activities. Sara Sheridan won the IMJR Young Writer Award by using lifelogging to understand media habits (and discovering hitherto unreported use of a mobile gambling website!)

The difference between Ethnography and Observation

Accompanied shopping trips have been called ‘shopalong ethnos’ while in home interviews are ‘home ethnographies’. They are both forms of observation. There is an important distinction.

Ethnography is the main research method of Cultural Anthropology; the study of human culture and social organisation. Its focus is very much on the social and cultural implications of the behaviour.

- The ethnographic method very often works within a community and includes participant observation, interviews, documentary analysis and other sources of data to build a holistic picture.

Ethnographic research is characterised by:

- Focus on social and cultural context

- Seeing the world from the participant’s point of view (an Emic perspective)

- Observing behaviour at the time and place where it actually occurs

- Use of a range of data collection methods, including interviews, informal conversations, participant observation, photographs, films, and other cultural artefacts.

Through the narratives of ordinary people it can show how society is structured, how people interact within their roles and relationships, and how ownership of products acquires significance over and above their practical value. Used in this way, its findings can be far reaching and powerful, but will normally require a lot of fieldwork and analysis. See: Bhangraamuffin Style, Philly Desai, Qualitative Research in the 21st Century AQR /QRCA 2001

An ethnographic interview is likely to focus on cultural, social and behavioural questions

- Grand Tour questions – what are the places, people, procedures like? Who does what and why? How are things structured? What is important to people and how do you get things done?

- Detail questions – focus on incidents or artefacts of significance. In what ways is this important?

- Experience questions – how does it feel to….? What activities do you do? If it takes place after an observation it can be a detailed deconstruction of what happened.

- Language and belief structure questions – how do you greet various types of people? What subjects can you /not discuss? How do people understand who is successful and powerful? How do you talk about religion, politics etc.?

Observation is focused more on the practical and brand-related implications of the behaviour. It covers many things that are never discussed in face to face research, because they can’t remember, there is no context to stimulate recall, or they think these things are unimportant.

- What procedures and processes are used and how they vary from one person to another.

- How products are used and misused, and how they fit into the processes.

- How social interactions between people affect choices and behaviour.

- How the physical context (layouts, cupboards, workspaces, etc.) shapes usage and behaviour.

An observation guide should include notes about the use of space, people and interactions, tools, things and processes as well as the questions from the discussion guide.

Workshops

The workshops we use now arose from a 19th century cooperative philosophy to support workers’ rights. Our workshops still bear the hallmarks of a democratic and participatory process. Although clients and workshop leaders sometimes aim to game the outcome they want, it’s quite hard to manipulate the workshop. The ‘results’ arise from the interaction between participants, and genuine interactions reveal genuine needs.

A genuine workshop is a well-designed process with a number of characteristics:

- Participants in workshops are active rather than reactive

- Therefore they are more likely to buy in to the outcomes

- The role of the facilitator is to set tasks, and manage the process to allow participants to express their own agenda and their own content

- Workshops thrive on difference and diversity whereas groups need homogeneity

- Workshops can have a positive effect on team building

- Workshops offer a chance to discard or ignore previously established roles as many techniques are democratic

- Workshops allow flexibility to work with different sizes and structures of groups in one session

- Workshops allow movement, the use of techniques, more extensive and developmental stimulus material than you could use in a group discussion.

- You can set up a workshop to solve a problem without having any definite idea where the answer will lie. Problem definition can be part of the workshop.

- Workshop facilitators do their best to create a process to answer the workshop objectives, but are not responsible for the content. The participants create the content.

In practice, whatever the overt purpose of the workshop, it will have ‘collateral benefits’ which will include knowledge and information sharing, creative thinking, teambuilding and creating open-ness to change

Drawbacks of workshops

- Workshops can be expensive and time consuming to organise.

- They need to be planned and managed well and can go horribly wrong if they are not.

- They need commitment from participants and a genuine desire to listen openly on behalf of the client.

Differences between groups and workshops

A group Moderator works in a Question-response model, using process and techniques to help optimise the content that comes out. Moderators are responsible for producing the content – the findings.

A workshop Facilitator may use some moderating skills (but needs many others) and works by setting tasks, managing the activity and helping participants clarify and summarise the content they have created.

Facilitation Skills Self Assessment – a quick two pager that will give you a realistic idea of what is involved

QM Workshop Planning Template – all the practical and process things you have to consider. The plan is the secret weapon; it keeps you on objectives, on time, well-resourced and calm. And if things do go pear shaped, you can negotiate with the participants as to how to use the time most productively.

- An indispensable resource for running all kinds of workshops

- Downloadable, and hyper-linked so you can find tools and techniques quickly and easily

- Workshops come from the Co-operative Movement. The philosophy is about empowering people.

- Being a group moderator is a good start, but not enough. Discover what other skills you need.

- What are the common anxieties about facilitation? The manual shows how to manage them.

- How to set goals and define problems

- Planning a workshop from invitations to follow ups, step by step

- Creating an engaging and productive day plan

- Specific tools for managing people

- Tools for activating research findings

- 20 icebreakers, 10 energisers, 10 tools for enabling thinking differently, 18+ tools for idea generation, 10 tools for idea evaluation, 10 tools for process planning and problem analysis, 8 tools for ending.

- 109 pages including reading list and links to websites for further inspiration

Other Collaborative Methods

Deliberative methods are a hybrid between public consultation and research. They usually involve political, social and economic issues and are used to inform policy. Rather than just discover what people think or feel, they bring in additional information about the options and allow people to debate it before presenting their view. The information can come through experts, leaflets, briefing sessions, presentation of scenarios, etc.

They are used for complex subjects where there are many options and trade-offs. They can run over several days and/or include a series of techniques, including citizen’s juries, polls, consensus conferences and deliberative workshops.

Community consultation – People’s panels, area forums etc.

Going under a variety of names, including Service User groups, these are most often used by councils and local authorities for consultation with residents. They very often consist of a large number of local residents (who tend to be volunteers and may not be representative of the area), with whom the council can conduct both qualitative and quantitative research.

These are often more representative if they are set up by research companies working for local authorities. Research shows that citizens consider referendums to be inviolable, but polls feel remote and faceless, and focus groups are not direct enough. Consultation panels are preferred as consultees feel more knowledgeable and feel they have some influence. However the problems with panels are attrition, conditioning and cynicism.

Consultation Methods are judged NOT by research standards

Residents prefer methods that

- Potentially strengthen the community

- Will change the community for the better

- Are able to hold the Council to account

- Have a guarantee of action

- Are representative and inclusive (Lovell and Henderson, Come Together, MRS 2000 Conference papers)

Open Space Technology for facilitation

Highly scalable and adaptable, OST has been used in meetings of 5 to 2,100 people. It is notable for NOT starting with a defined agenda – the participants create the agenda themselves. The approach is characterized by five basic mechanisms:

- a broad, open invitation that articulates the purpose of the meeting;

- participant chairs arranged in a circle;

- a “bulletin board” of issues and opportunities posted by participants;

- a “marketplace” with many breakout spaces that participants move freely between, learning and contributing as they “shop” for information and ideas;

- a “breathing” or “pulsation” pattern of flow, between plenary and small-group breakout sessions.

(Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide”, by Harrison Owen. Berrett-Koehler Publishers)